The Living Dead

Meet Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator, the bacterium that does it all: fix carbon, fix nitrogen, synthesize all essential amino acids, locomote — an organism that can exist totally independent of other life. It doesn't even need the sun. This fucker basically lives on sulfur, rock, and electrons*.

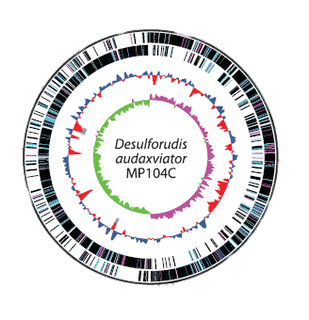

Meet Candidatus Desulforudis audaxviator, the bacterium that does it all: fix carbon, fix nitrogen, synthesize all essential amino acids, locomote — an organism that can exist totally independent of other life. It doesn't even need the sun. This fucker basically lives on sulfur, rock, and electrons*.It's an obligate anaerobe, without even the most rudimentary oxygen resistance. A bug like βehemoth would kick its ass throughout most of the terrestrial biosphere (its natural digs are a couple of kilometers down in the crust, where no O2 has poked its corrosive little head for at least three million years). But that's not likely to be any kind of drawback out in space, and various talking heads are already nattering excitedly about the prospect of something just like this hanging out on Mars, or on the Saturnian moons.

It is cool. It is, quite literally, a complete ecosystem bundled into a single species, a biosphere crammed into two-and-a-half megabytes and a crunchy shell. Astrobiologists the world over have been creaming their genes for a week now. It's such a science-fictional little beast that its very name was lifted from a Jules Verne novel— but what really sticks in my mind about this little Swiss-army knife is a feature that's actually pretty common down there.

If it's anything like other deep-rock dwellers, D. audaxviator reproduces very slowly, taking centuries or even millennia to double in numbers. It's a consequence of nutrient limitation, but might we be looking at a kind of incipient immortality here? The textbooks tell us that one of the defining characteristics of life is reproduction. But if you think of life as the propagation of organized information into the future — the persistence of signal, rather than merely its proliferation — then reproduction is really just a workaround. The chassis that carries the information wears out, and must be replaced.

It doesn't take much, here at the dawn of Synthetic Biology, to imagine an organism with unlimited self-repair capabilities; something that can keep its telomeres nice and long, which sweeps away all those nasty free radicals and picks up the broken bottles in their wake, which replaces an endless succession of disposable Swatches with a solid gold Rolex which can hang in there for a billion years or more. Hell, you could even postulate some kind of Lamarckian autoedit option on the genes, so the organism can adapt to new environments. Or you could just limit your organism to extremely stable environments that don't require ongoing adaptation. Interstellar space, for example. Or deep in a planetary lithosphere. In some ways, this could be a superior strategy to conventional breeding; at least you wouldn't have to worry about population explosions.

I wonder if, somewhere down there, D. audaxviator or something like it has given up on reproduction entirely. Maybe it keeps the machinery around as a kind of legacy app that no one uses any more and just ticks slowly onwards, buried beneath all that insulating and protective rock, unto the very end of the planet.

The textbooks would call it dead. I'd suggest our definitions may need an upgrade.

*Of course, the fact that it can live independently doesn't mean that it evolved independently. A bunch of its genes have been cadged from Archae via lateral transfer. Its genes also contain anti-viral countermeasures; whether it siphoned those off incidentally from donor species or actually uses them to guard against parasitic code, there's obviously a history of contact with other life in this bug's family tree.

Labels: biology, deep sea, evolution, extraterrestrial life